Migraine Australia Interview

Migraine Australia interviewed our Clinic Director, Roger O'Toole, for Migraine Awareness Month.

They discuss the the types of migraines we treat, if the neck drives the head pain or the head pain drives the neck pain, vestibular migraines, the Watson Headache® approach, concussion and some of the research we are doing on headaches and migraines.

Watch the full video below.

Latest Updates

Our Vestibular Migraine Case Series is

Published & Peer Reviewed

Our clinic director Roger O'Toole has successfully published the case series he co-authored with Dr Dean Watson, titled, "Manual Cervical Therapy and Vestibular Migraine : Case Series", and it has now passed peer review. The full version can be accessed here.

You are not alone

The reason why you, along with 80% of sufferers are looking for a better solution to your symptoms is because a significant part of the underlying cause is being ignored, or treated with techniques designed to treat other conditions.

Every person presents differently, from headaches, to dizziness, to nausea and vomiting and sensitivity to light and sound. Through a thorough assessment, we gain valuable insight into how your particular headache or migraine behaves. Understanding this enables us to diagnose more accurately, and, importantly, sets benchmarks for improvement.

Meet Cindy

Cindy was experiencing up to 60 headaches every day. Watch her story below.

Request a Free Pre-Assessment Call

Take control of your headaches and migraines book your free pre-assessment call now.

How do we help?

Using a technique known as the Watson Headache ® Approach, our consultants assess and treat a rarely diagnosed fault in the top of the spine, reducing your symptoms by normalising the activity in the brainstem.

Tell me more

The last two decades of research has identified the source of irritation in headache and migraine - the trigemino-cervical complex in the brainstem. This is the area that receives all the nerve signals from the trigeminal nerve (head and face) and upper three cervical nerves. We know that in recurrent headache sufferers regardless of type (migraine, tension-type headache etc) the trigemino-cervical complex is in a constant state of irritation, which in turn alters the response of our 'stress-response' system.

It is like a powder keg waiting for a spark.

This is why seemingly unrelated triggers - stress, hormones, sleep, skipping a meal, and getting in a hot car, can all cause problems. They are all 'stressors' that interact with, and 'blow up' the powder keg.

The medical approach focuses on avoiding triggers, and using drugs to dampen the activity. Unfortunately, things that happen everyday 'stress' your body and you can't avoid all of them, all of the time. Medications alter the function of neuromodulators (serotonin, noradrenaline) and our acute inflammation responses (CGRP) we require for healing, leading to potential side effects impacting on the gut, brain function and even, amazingly, more headaches!

Only treatment aimed at lowering the over-activity of the brainstem can claim to be treating the underlying problem. Groundbreaking research from Dean Watson's PhD shows that is exactly what our treatment does. The neck not only connects directly to the headache centre, but also the vestibular centre (dizziness, vertigo), solitary nucleus (nausea, blood pressure, metallic taste, acrid smells) and locus coeruleus (alertness, memory, sleep, brain fog). During your assessment we will determine if your neck is causing irritation. Whilst many of you will have neck symptoms and know that it is part of the problem, 30% of the people we treat experience no neck symptoms at all.

Request a Free Pre-Assessment Call

Take control of your headaches and migraines book your free pre-assessment call now.

What we treat

Migraine is the most common condition we treat at the Melbourne Headache Centre, which is not surprising given it is the leading cause of disability in people under the age of 50 worldwide!

30% of our patients have almost daily symptoms spread across a number of conditions from chronic migraines and chronic tension-type headaches, to new daily persistent headache, hemicrania continua and persistent postural-perceptual dizziness.

Not only do we see significant results providing treatment for different forms of migraine, including migraine with aura and vestibular migraine, but as a niche clinic highly focussed on disorders of brainstem sensitivity we have developed expertise in a range of other conditions that many other clinics won't have even heard of. These include less common primary headache disorders such as cluster headache, hypnic headache, exertional headache, as well as conditions 'associated with migraine' such as cyclic vomiting syndrome, abdominal migraine, hyperacusis, chronic non-allergic rhinitis, and central sleep apnoea.

The neck is a well known source of headache with cervicogenic headache, whiplash associated disorder and persistent post-concussion syndrome being more obvious conditions associated with neck dysfunction.

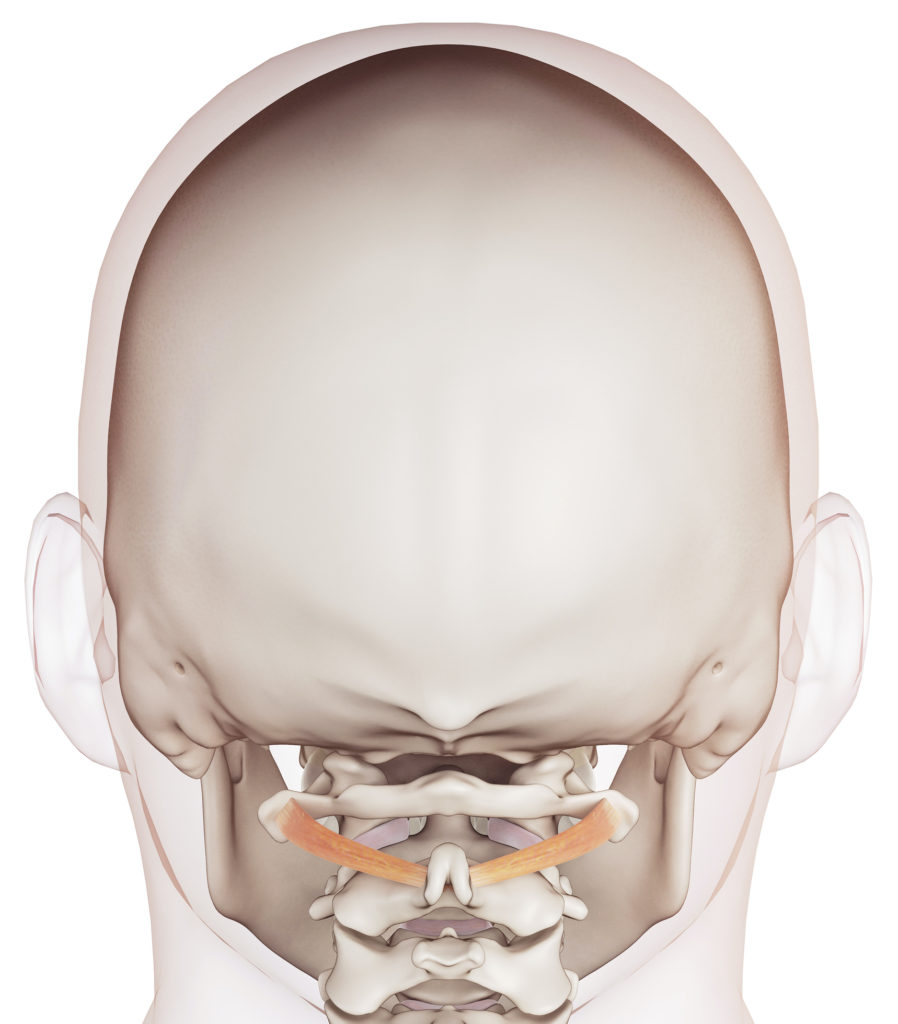

However, the small muscle in the top of your neck provides a critical link between your head and body helping to control startle responses, balance, and blood pressure when rising. Small faults in the neck cause disturbances in these sensitive little muscle that can lead to symptoms beyond headache, nausea and dizziness, such as those associated with syncopal migraine (fainting with the migraine) and external vertigo (visual disturbances - visual lag, visual tilt and oscillopsia) commonly seen in vestibular migraine.

Who Are We?

Our team of physiotherapists, have undergone specialised training in the Watson Headache® Approach.

90% of people we treat with this approach suffer with headaches or migraines, so we have a unique understanding of the struggle that people with migraine face every day.

We understand how debilitating this 'invisible' disease is, and nothing gives us more joy than when our clients tell us about the positive impact we are making in their lives.